Heavy, repetitive resistance training wasn’t designed with joint health in mind. Sooner or later, you’ll find that something hurts in your shoulders, knees, elbows, or hips. Many of us just push forward, until that something really hurts. Oftentimes, that’s your first introduction to the itis family: tendonitis, bursitis, arthritis, and so on.

Instead of enduring discomfort or downing over-the-counter medications to relieve pain, let’s instead focus on 11 ways you can make the workouts you’re already doing easier on your joints.

Even if you don’t have pain now, heeding these recommendations can help keep you in the gym and off the sidelines.

1. If It Hurts, Don’t Do It. Look for Similar, Alternative Exercises

A sports-medicine doctor will tell you that if an exercise hurts, don’t do it. But that doesn’t mean you have to abandon that movement pattern altogether. For instance, people with shoulder issues (count me in!) often have problems with barbell presses. The shoulders are locked in one position, leaving little room to work around pain.

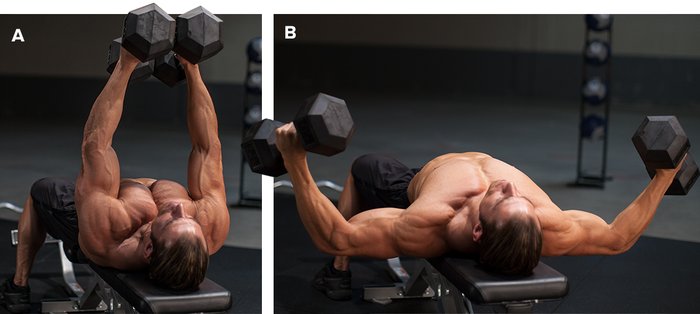

A multijoint move like the bench press might aggravate a sore shoulder, so try an isolation exercise like a chest fly or cable cross-over, and see how that feels. They’ll activate the pecs, but alter the motion. You could even change the angle you’re working.

If your shoulder hurts when benching, one option is to try chest flies, a single-joint movement.

But there are more options. ”Instead of an overhand grip bench press, try underhand.” suggests Guillermo Escalante, DSc, ATC, CSCS, owner of SportsPros Physical Therapy Center in Claremont, CA. “Dumbbells are also a great option, because they offer more freedom of movement. Move just a few degrees of shoulder abduction or adduction, and all of a sudden, what was a painful movement doesn’t hurt anymore.

“On top of that, newer research shows that because there’s more instability with the dumbbells, the muscle has to activate more,” he adds. “Because you’re having to stabilize the dumbbells, you won’t need as much weight to achieve the same level of activation.”

2. Use Smooth, Controlled Motions, And Avoid Bouncing

Any exercise that allows for body English and momentum also allows you to use heavier weights than you normally would with strict form. Nothing aggravates a sore joint more than putting excess weight on the bar and then using bad form.

“If you’re bouncing out of the hole when doing squats, thrusting through your hips to complete barbell curls, or jerking the weight on rows, you’re stressing your joints, ligaments, and tendons,” says Escalante. His recommendation: Reduce the load and start working on technique while using a smooth, controlled motion.

3. Consider Using Free Weights Instead of Machines

Machines have their pros and cons. A novice lifter who can’t balance a weight very well might require a machine in order to complete a movement. However, the machine forces you to work in only one direction, not allowing your joints much freedom of movement. Try doing a similar move with a barbell, dumbbells, cables, or bands.

4. Make Sure Your Warm-up Is up to the Task Ahead

Being told to warm up always feels like Mom is nagging you to brush your teeth. But it’s sage advice, especially as you age. Warm-ups not only allow you to push more weight in the gym—and shouldn’t that be reason enough?—they gradually loosen up muscles and connective tissue, improving your range of motion and flexibility.

“Warming up increases the dilation of blood vessels, blood flow to the area, and neural activation of all of the muscles you’ll be recruiting,” says Escalante. “Do a 5- to 10-minute cardio warm-up to get your heart rate elevated along with some very light warm-ups sets of your initial movement, but don’t take them close to muscle failure. Save the static stretching for post-workout, but dynamic exercises can also be helpful.”

5. Focus on Time Under Tension Rather Than Training to Failure

“If you’re constantly training to failure—even if it’s light endurance loads—you’re going to have some joint issues,” warns Escalante. “That’s why pushing yourself to just short of failure is a good strategy for at least some of your workouts.”

Training to failure is often accompanied by mild breakdowns in proper technique, he adds. The load in and of itself may not be problematic for joints, so long as you’re not breaking down your mechanics during the lift. For building muscle, however, though. “There’s recent research that indicates hypertrophy is linked to time under tension, rather than loading up as much as you can and doing a 6RM,” Escalante says. “I’d rather do a 12RM, keeping the muscle under tension the whole time and using a slow, controlled motion.”

6. Limit Intensity-Boosting Techniques to Particular Training Cycles

“We hardcore lifters like to push hard, beyond failure, at every workout, and that’s what a lot of intensity-boosting techniques are for,” says Escalante. “If you’re always pushing to the limit, something’s going to give—like your joints. Using a periodized scheme, in which you alternate your loads, is probably the smartest way to avoid this. You can still stress your body, but there are also periods of active recovery cycled in that aren’t as strenuous, and you’re not training to failure all the time.

“I’m a big fan of an undulating model of periodization,” he adds. “Instead of having weeks dedicated to lighter lifting, hypertrophy, or lifting super-heavy, I prefer to include all those within just one week.”

7. Let Pre-Exhaust Lighten the Load

In most cases, you begin your workout with a foundation compound exercise, like squats, bench presses, deadlifts, or overhead presses. But with pre-exhaust, you position a single-joint exercise like leg extensions before squats; this pre-fatigues the quads before you start the squats. If squats were done first, you might have to use 405 pounds to fall within the hypertrophy rep range; after a pre-fatigue, you might instead be able to get away with using 315 pounds and still stay within the 8- to 12-rep range. That decrease in load means a decrease in joint stress.

Single-joint leg extensions done before squats serve as a pre-exhaust, meaning you won’t be going as heavy on the latter.

“I like pre-exhaust, because you don’t have to use as much load in your compound exercises,” says Escalante. “[The reversal of exercise order] might also give the joints and target muscles more time to warm up, as you don’t use nearly the same heavy loads with a single-joint movement as you would with compound exercises. Being a little tired going into a ‘big’ movement means you won’t have to put as much weight on the bar. Yet you’ll still get all the activation you need.”

8. Favor Techniques That Slow Rep Speed and Minimize Momentum

Not all intensity-boosting techniques require near-maximal loads; slowing down rep speed is a simple way to take pressure off joints. “Any time you’re slowing down a movement, you’re putting more stress on the muscle and taking it off the joint itself,” says Escalante. “Controlling movements puts the stress on the muscle, which improves hypertrophy. It also reduces momentum, which is how you often get these injuries. Reducing rep speed usually means lowering the weight.”

One notable technique that does this is called reverse movements, which minimize elastic energy by pausing at the bottom of a movement for a few seconds. This technique is especially useful for increasing strength over the bottom portion of the range of motion.

9. Avoid Locking Out Your Joint

Conventional wisdom is to take a movement to the end of the range of motion. But when you lock out a joint, most often done with multijoint chest movements as well as triceps and leg exercises, the load instead shifts to the joint itself.

“Now you’re putting all of the tension on the actual joint, and the muscle becomes unloaded,” says Escalante. “At the joint, you’re getting maximum surface contact between the two adjoining surfaces. This is especially unwise if you have, say, 500-1,000 pounds on the leg press. It also reduces time under tension, meaning you’re doing so at the cost of muscle gains.”

If you’re already got knee pain, for example, Escalante warns that those last 10 degrees of extension have maximum surface tension, which could grind away the patella. If you do leg extensions, the first 10 degrees can also contribute to knee pain. “My advice is to stick to the middle of the range of motion,” he says.

10. Use NSAIDs and Prescription Medications Sparingly

It’s not uncommon for lifters to take an over-the-counter anti-inflammatory or analgesic before workouts to take the edge off nagging pain like tendonitis or joint pain. One downside to masking the pain is that you may be causing further damage without knowing it—at least, until the medicine wears off. Another downside is that chronic use of these meds can be hard on your liver.

11. Boost Intensity Gradually

While most lifters looking to increase muscle size typically train in the 8- to 12-rep range, that doesn’t mean they won’t sometimes try for a max lift or decide to work on strength for a while. That can mean an additional 50-75 pounds on the bar. That’s a significant increase in force on your muscles and connective tissue, as well.

“If you’re considering making big changes in your training and expecting muscle adaptation, give your body an adaptation phase,” says Escalante. “If you’ve been training at 12RMs, first go down to 10RMs for a little bit, then down to 8RMs for a while, and then 6RMs. Once you become accustomed to those heavier loads, you can easily alternate between a 4RM and 10RM workout.”

Escalante also notes that when entering a growth or strength phase in your routine, tendons and ligaments grow more slowly than muscle tissue. “They can become a weak link in the chain and are at greater risk of injury,” he says.